The Timeline highlights significant developments in the history of financial regulation against U.S. and world events. Choose a different decade below, or scroll down to discover more.

In January, the SEC required broker dealers to begin keeping systematic transaction records and make them available to the regional offices upon request. By mid-1940 the regional offices had conducted 560 broker dealer inspections. Most early violations, regional offices found, stemmed from negligence rather than intentto defraud.

In 1940, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission brought actions against nine of the thirteen largest public utilities holding companies. By 1943, it had instituted actions against almost all major utility companies. These actions led to greater plant efficiency, lowered customer rates and increased shareholder value.

Enacted on August 22, the Investment Company Act required organizations engaged primarily in investing and trading stocks to give full disclosure about investment objectives and minimize conflicts of interest. The Investment Advisers Act required investment advisers to register with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission before providing services. Congress, concerned about the effect of widespread redemptions on the market, placed limits on the size of mutual funds, but the industry gained the ability to maintain retail prices of funds.

A national committee of investment companies formed to help shape the Investment Company Act of 1940, and became a permanent association in 1941. In 1961, the National Association of Investment Companies (NAIC) was renamed the Investment Company Institute (ICI); in 1970, ICI relocated to Washington, D.C.

After lengthy negotiations, the SEC persuaded the New York Stock Exchange to suspend this rule—imposed in the 1930s but only recently enforced—intended to protect the NYSE monopoly by preventing members from trading in listed securities on other exchanges.

The New York Stock Exchange began a roll-back of governance reforms with the creation of the Board of Governors Advisory Committee. Over the next two decades, control of the exchange returned to floor members.

The National Association of Securities Dealers promulgated an uniform practice code, setting standards for listing and delivery of securities.

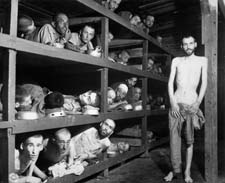

As an agency considered non-essential to the war effort, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission relocated to Philadelphia. One-third of its staff left for military service. The SEC returned to Washington, D.C. in 1948.

On May 21, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 10b-5. This rule, triggeredby a Boston Regional Office investigation, extended the definition of fraud beyond sales of securities to purchases as well. Rule 10b-5 has subsequently served as the cornerstone of SEC insider trading actions.

In a case involving wheat farmers growing grain for home use, the U.S. Supreme Court expanded the applicability of the commerce clause to include a broad range of activities, if they had a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission proposed revisions to rules governing proxy access, allowing shareholders greater role in the nomination of directors. Widely opposed by business, the changes were not adopted.

The 1933 Act allowed the Commission to offer conditional exemption from full registration to issuersof up to $100,000 in securities. On April 22, 1938,the SEC adopted Regulation A, enabling small issuers to file limited exemption documentation. By 1943, “Reg A” exemptions accounted for a large part of the workload at many regional offices.

In its Charles Hughes v. SEC decision, the Second Circuit upheld the SEC’s “shingle theory,” asserting that any securities firm “that holds itself out as competent to advise” must disclose market prices. Although the Hughes case, brought by the New York Regional Office, was not the first case to draw upon shingle theory, it marked the point at which the concept became accepted within American jurisprudence.

Delaware General Corporation Law Section 61-b limited shareholder derivative actions against a corporate board by requiring a plaintiff to own at least 5% of a corporation’s shares or more than $50,000 in stock. This state statute provided a template for some of the restrictions on securities fraud class actions introduced by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) in 1995.

In its Public Service Company of Indiana decision, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission overruled a National Association of Securities Dealers disciplinary measure, finding that enforcing minimum prices was not a legitimate role for a self-regulatory organization.

In IRS v. Shamberg's Estate, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the immunity from taxation of Port of New York Authority bonds. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case, allowing the constitutional barrier to federal taxation of municipal bonds, established in its 1896 Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust decision, to stand.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission attempted to prohibit the practice of New York Stock Exchange members trading purely for their own accounts. Such trading gave members an advantage over public customers and increased market volatility. In 1945, when the SEC voted to abolish proprietary floor trading, the White House ordered it to rescind the rule.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission previously had accepted the pronouncements of the American Institute of Accountants' Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP) as generally accepted accounting principles. But in ASR No. 53, the SEC limited the application of CAP's Accounting Research Bulletin 23 on accounting for income taxes. Over time, the SEC modified its view and did not enforce ASR No. 53.

On July 23, James J. Caffrey, who had served two years as regional administrator in Bostonand seven as regional administrator in New York, became Chairman of the SEC. Although Caffrey served only one year as chairman, his appointment marked the beginning of a 25-year period in which regional offices enjoyed a great deal of autonomy within the Commission.

The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in SEC v. W.J. Howey defined a "security" under federal securities laws. It provided for the test for the existence of an "investment contract," one of the most important instruments listed in the statutory definition of a security.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission allowed the National Association of Securities Dealers to register individual broker representatives, in addition to broker-dealer firms, expanding the NASD's authority over the industry.

Eleven years after the passage of the Public Utilities Holding Company Act, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's power to break up utility holding companies.

In 1943, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, writing for a slim majority, held that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission abused its discretion by finding that inside traders of Federal Water Service Corporation were "fiduciaries under a duty of fair dealing." In U.S. v. Chenery's second appearance before the Court, Frankfurter's limited vision of administrative law was rejected by the majority, led by Justice Hugo Black. The Court held that the SEC may engage in either general rulemaking or ad hoc litigation in individual cases, within the discretion of the agency. The Court thus deferred to agency discretion, a bedrock principle of modern administrative law.

Congress passed the Administrative Procedure Act, establishing legal procedures and requirements for administrative action, including requirement of "substantial evidence" and providing for judicial restraint of "arbitrary and capricious" decisions.

With the workload ofthe SEC’s ten regional offices increasing, during fiscal year 1947 the Commission established satellite facilities, which handled investigatory work, in Detroit, Los Angeles, St. Paul, Tulsa, and St. Louis. Each “branch office” reported directly to a Regional Administrator.

The Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, known as the Hoover Commission after its chair, former President Herbert Hoover, reported that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission had a backlog of unreviewed corporate reports and was unable to examine brokers on an annual basis, in part due to the shrinkage of the agency's staff and budget following World War II.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission disagreed with the American Institute of Accountants' Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP) over whether unusual and extraordinary items were best displayed before net income, in the SEC's view, or after net income, in the CAP's view in its Accounting Research Bulletin 32. The SEC Chief Accountant announced that the SEC would take exception to financial statements that appeared to be misleading, even if they reflected the application of CAP's bulletin.

As part of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's investigation of start-up automobile manufacturers following World War II, Preston Tucker and executives of the Tucker Corporation were indicted in federal court. The government contended that Tucker, while raising over $15 million through an initial stock offering and dealership sales, never intended to produce a car. While the court found the defendents not guilty, the Tucker Corporation went out of business.