Home >

Galleries > Chasing the Devil Around the S... > The Four Horsemen and Jones v....

Chasing the Devil Around the Stump: Securities Regulation, the SEC and the Courts

A New Era Unfolds

The Four Horsemen and Jones v. SEC

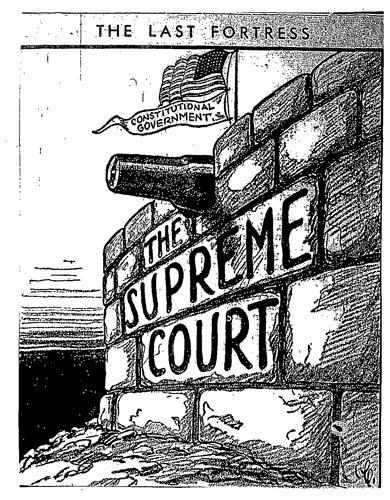

February 25, 1937 The Last Fortress

Yet the path for a new regime of regulation was not easy. The Supreme Court, with four conservative justices -- Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter -- continued to decide cases based on the substantive due process protection of contractual and property rights. They often convinced one or more fellow justices to form a majority to defeat new attempts at property regulation. As New Deal laws regulating business came before the Supreme Court, the conservative majority, protecting property rights, struck many of them down as unconstitutional violations of the delegation powers or the interstate commerce clause. The conservative four at the heart of these denials came to be referred in apocryphal admonition as the “Four Horsemen.”

These actions posed immense problems for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sought to use its broad statutory authority to regulate individual and company property rights in every state of the nation. Facing this dilemma, the SEC deftly moved cases of its own choosing to the Court with arguments they hoped would reverse the Court’s anti-New Deal and anti-regulatory majority.

The SEC found intellectual support in Justice Louis Brandeis’ dissent in the 1933 case of Liggett v Lee, in which Brandeis, realizing the effect of the conservative majority philosophy on increased administrative regulations, attempted to reformulate the argument. The case involved a Florida attempt to tax chain stores, generally constituted by larger national retail chains, in a greater amount than individual, locally-owned stores. The chain stores challenged the regulation as arbitrary and unreasonable, and thus unconstitutional. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the conservative majority, agreed with the chain stores that the state regulation was unconstitutional.

Justice Brandeis dissented, arguing that the legislative goal of “protecting the individual, independently-owned, retail stores from the competition of chain stores” was valid. He argued that Florida was regulating corporations in intrastate commerce, and that the state had acted entirely within its powers. “Limitations upon the scope of a business corporation’s powers and activity were …universal,” and thus, “the difference in power between corporations and natural persons is ample basis for placing them in different classes.” Brandeis wanted to show that the power of huge national corporations, which he believed controlled and mismanaged much of the reeling economy, should be a proper constitutional basis for regulation. Proponents of New Deal administrative regulatory reform cheered. The SEC, arguing cases in lower courts as they made their way to the Supreme Court, hoped that the Court majority would adopt a position on securities issues consistent with Brandeis’, instead of the conservative majority’s, argument.28

As the SEC’s cases moved through the appeals process, the agency searched for one to test the constitutionality of the Securities Acts. It believed it had found its case in Jones v. SEC.29 Jones, an issuer of stock under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, filed a registration statement with the SEC stating his intent to offer stock for sale. SEC staff members questioned the accuracy and completeness of the statement, issued a stop order, and subpoenaed records of Jones regarding the statement. Before the hearing, Jones withdrew his registration and refused to proffer the subpoenaed records, insisting that he could voluntarily withdraw the statement and effectively deny the SEC’s continuing jurisdiction and the constitutionality of the federal acts. The SEC, cognizant of this challenge to their investigative powers, appealed.

The Supreme Court, with Justice George Sutherland writing the opinion, disagreed with the SEC. Sutherland analogized that the SEC, as an administrative agency, had the same power of a court to order that Jones appear and give testimony, but it could do so only if the SEC was acting “in the public interest and for the protection of investors.” Since the sale of the stock had been withdrawn, and therefore there was no threat to the public or potential investors, Sutherland and his six-justice majority found that the SEC had acted beyond the scope of their authority. Their ruling compared the agency to the infamous “star-chamber” of English history.30

Justices Brandeis, Harlan Stone and Benjamin Cardozo dissented. “Recklessness and deceit,” wrote Cardozo, “do not automatically excuse themselves by notice of repentance.” The dissenters believed that the misrepresentations made by Jones in the registration statement vested the right and power of the SEC to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute any violations. After losing the first case the agency appealed to the Supreme Court, the SEC faced a restricted interpretation of its powers that, if successful, could undermine the agency’s ability to investigate and prosecute wrongdoing.31

<<Previous Next>>

Footnotes:

(28) Liggett v. Lee, 288 US 517 (1933), 517-548.

(29) Jones v. SEC, 298 US 1 (1936); Noah Feldman, Scorpions (Twelve Publishing: New York, 2010), 71-102.

Related Museum Resources

Papers

- March 21, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 22, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 22, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 23, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 23, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 31, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- April 4, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- April 12, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- April 18, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- July 29, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- August 9, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- October 22, 1932

-

transcript

pdf

(Willis Van Devanter Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- March 14, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 15, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 18, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 20, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 21, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 25, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 27, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- May 15, 1933

-

transcript

pdf

(With permission of the Pierce Butler Family Papers, Minnesota Historical Society)

- January 4, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 4, 1934

-

image

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 20, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(William H. Moody Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 26, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(William H. Moody Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- March 16, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- March 31, 1934

-

image

pdf

(Hugo Black Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- April 5, 1934

-

image

pdf

(Hugo Black Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- April 9, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(William H. Moody Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- April 16, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(Hugo Black Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 1, 1934

-

image

pdf

(Hugo Black Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 11, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(With permission of the Pierce Butler Family Papers, Minnesota Historical Society)

- August 5, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- December 19, 1934

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- January 10, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 11, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 11, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 12, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 12, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 12, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 13, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 14, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 14, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 15, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 15, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 18, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 23, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 4, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 6, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 7, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 12, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 19, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 19, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 19, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 20, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 20, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 22, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 1, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(With permission of the Pierce Butler Family Papers, Minnesota Historical Society)

- May 27, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 28, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 28, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 28, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 1, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 1, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 1, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 3, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 5, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Louis D. Brandeis Papers, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville)

- June 17, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- December 5, 1935

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- December 17, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

- December 24, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

- December 24, 1935

-

image

pdf

(Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

- 1936

-

image

pdf

- January 14, 1936

-

transcript

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 3, 1936

-

image

pdf

(Stanley Forman Reed Collections, courtesy University of Kentucky)

- February 4, 1936

-

transcript

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- February 20, 1936

-

image

pdf

(Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

- April 24, 1936

-

transcript

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- May 27, 1936

-

transcript

pdf

(Harlan Fiske Stone Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- June 27, 1936

-

image

pdf

(Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

- 1937

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 9, 1937

-

transcript

pdf

(Charles Evans Hughes Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

- January 29, 1937

-

transcript

pdf

(William H. Moody Papers, courtesy Library of Congress)

Photos

- February 8, 1935

-

Joseph Parrish cartoon, published in The Nashville Tennessean

(Courtesy Library of Congress )

Oral Histories

18 September 2007

Paul Windels, Jr.

With Dr. Kenneth Durr

-